|

Tiger

Software Blog

Send any comments or questions |

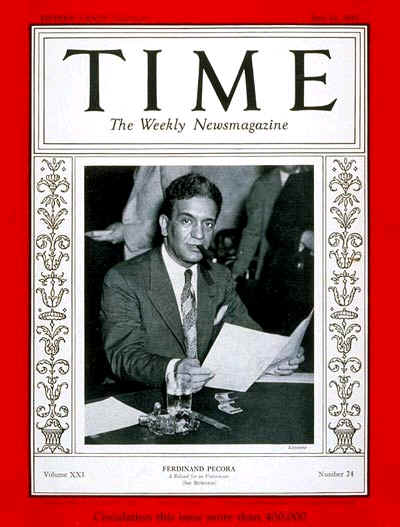

| Ferdinand Pecora: American Hero Obscene executive bonuses, Ponzi schemes, excessive leveraging, self- serving lies, false rumor mongering, knowingly bad recommendations, front-running, flagrant stock manipulation, pools and bear raids without having to borrow stock, Swiss bank accounts, cozy relations between regulators and the regulated, income tax avoidance, credit rating company lies, ubiquitous insider trading, millions from Wall Street to bribe and buy Congress... Out of control greed and Gilded-Age extremes of wealth and poverty. out--of-control greed.... Is this what America has come finally too? All this is what we know now. How much worse is the full truth about Wall Street? Until there is a thorough, outside investigation of Wall Street, investor confidence will remain shattered. Rallies will fizzle and regulatory agencies will be mere window-dressing. We need another Ferdinand Perora. He was the Senate investigator in 1932 who broke open for public viewing the widespread corrupt practices that lay behind the Crash of 1929 and prolonged the Depression, by shattering investor confidence in Wall Street. Congress needs to thoroughly investigate Wall Street. Obama is silent. His rise to power depended on Wall Street money. Congress is knee deep in Wall Street bribes (campaign contributions.)  Time June 12, 1933 Pecora, the quintessential outsider, challenged and exposed the corrupt world of Wall Street insiders, swindlers and good-old-boys. His investigations paved the way for the Securities and Exchange Commission and the healthy separation of banks from brokerages and investment banking until 2000. Ferdinand Pecora (January 6, 1882 – December 7, 1971) Born in Nicosia, Sicily. He earned a law degree from New York Law School and eventually worked as an assistant district attorney in New York City, during which time he helped shut down more than 100 bucket shops. He was a Progressive Republican when he was appointed Chief Counsel to the U.S. Senate's Committee on Banking and Currency in the last months of the Herbert Hoover presidency by its outgoing Republican chairman and then continued under Democratic chairman Duncan Fletcher, following the 1932 election. In these hearings, the Senate Committee and Pecora probed the causes of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Pecora, personally interrogated such high-profile Wall Street characters, as Richard Whitney, president of the New York Stock Exchange, George Whitney a partner in J.P. Morgan & Co. and investment bankers Thomas W. Lamont, Otto H. Kahn, Albert H. Wiggin of Chase National Bank, and Charles E. Mitchell of National City Bank. The popular name for these hearings was the Pecora Commission,

Pecora's investigation unearthed evidence of banking practices that greatly

enriched

Many elements were responsible for the backsliding that led to these scandals, not least the Republican Party. The decline of regulation began in earnest with Ronald Reagan's inaugural address, in which he famously noted that "government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem." Guided by excessive faith in "the free market," regulators in the SEC, the Fed, the NASD (which merged in 2007 with the regulatory arm of the New York Stock Exchange to form the Financial Institution Regulatory Authority), and other agencies had simply stopped doing their jobs. Even during the Clinton administration, the craze for deregulation had so worked itself into the national culture that Congress blocked major accounting reforms pertaining to stock options, and, in 1999, Clinton's financial advisers supported the very ill-advised repeal of Glass-Steagall. Worse, in 2000 they accepted the catastrophic exemption of credit-default swaps from any regulatory oversight at all. By the time George W. Bush became president in 2001, the SEC's strategy of transparency had been thoroughly undermined. The return of opacity was in full swing. The elements of a perfect storm were in place, and, by 2007, Bush's policies had brought them all together for the explosion of 2008. While all this deregulation was going on, the financial services industry had found even more new ways to circumvent transparency. An unregulated shadow banking system arose, through hedge funds, private-equity funds, off-balance-sheet operations, offshore tax havens, and the widespread trading by money managers in completely opaque instruments, especially credit default swaps. Because of the enormous profit potential in these securities, the movement of vast sums from the regulated sunshine to the unregulated shadows became inevitable. Today, banks and other institutions have a very uncertain idea of what their holdings of the new instruments are actually worth. Therefore, they cannot accurately calculate their own assets and liabilities, let alone those of others. This is why they are so reluctant to lend, and why the nation's credit system remains in gridlock despite the $700 billion bailout. Opacity has thus turned inward upon the very institutions that created it, which would be an ironic farce if its consequences weren't so tragic.

Obviously, there is much work to be done. The SEC still has an acceptable structure, but it needs robust infusions of talent, expertise, and money. The staffs of both the Fed and its twelve regional banks are far more sophisticated now than they were during the 1930s, and the fdic is working well under Sheila Bair, one of the few people who began warning years ago of potential catastrophe. But banking regulation remains extremely fragmented, with far too many players: the Fed, the fdic, the Comptroller of the Currency (a part of the Treasury Department), dozens of state banking commissions, and still other agencies. They are in desperate need of better coordination and, possibly, consolidation. What's more, the regulatory talent emblematic of the New Deal is not gone altogether, but it is thinner to the point of anorexia. After years of ideological hiring, large clusters of ineptitude bedevil the SEC, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the Department of Justice, and many other federal bodies. Nearly every important agency has long been starved of resources--and even of the elementary belief that regulation is necessary. The political opposition to reform will be stiff. The Republican Party will likely fight every step of the way. So will the financial services industry, some of whose stalwarts are Democrats. Even now, Wall Street remains in deep denial: The lavishing of billions in executive bonuses by firms that received federal bailout money is all we need to know about this industry's feral determination to protect its outrageous pay scales. Source: http://www.tnr.com/politics/story.html?id=686e3d61-aa6f-4431-acac-d067fe28ed8e&p=4

|

|

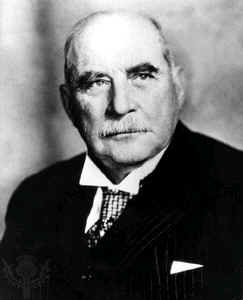

Imagine being in the audience on a hot July afternoon when Pecora questioned JP Morgan. Pecora was being paid just $225 a month! |

Has Morgan paid any income tax in 1930? Morgan mumbled

Has Morgan paid any income tax in 1930? Morgan mumbled