|

Bush today called for $145 billion worth

of tax incentives for business investment and quick tax relief for

indiviiduals. Bush just loves tax cuts for the

wealthy, doesn't he? Bush is using the recession to push his solution

for everything economic. But is it enough? Will it be

spent? Will the Democrats go along with it? Will there be

new business investment if

confidence is so low? Will it end up just being a tax break mainly for business

investment

already planned? On the individual side, will it go

primarily to the wealthy, who spend much lower percentage of

their income.

Bush's proposals totally fail to address UNDER-CONSUMPTION as a primary cause for

the recession.

The poor have very little to spend and the dwindling middle class are

fully tapped out. Many have exhausted their

credit cards. A tax credit of $300 will be quick fix, but be of very

liitle long-term help to them, if they can't make their

morgage payments and are paying hundreds of dollars more a month for

gas.

The problem as I see it is that the rich have most of the money in the US. The wealthiest

one per cent of

the population owns more than the bottom 95 per cent. The rich

don't need tax cuts and won't spend the tax rebates.

Whether measured in terms of annual income, percentage of financial assets

owned, or the earnings of corporate executives compared to ordinary workers, the

incontrovertible evidence shows that more and more economic resources are controlled by

fewer and fewer people. One study revealed that the percentage of total household wealth held by the top one

percent of families grew from twenty percent in 1976 to over forty percent in 1997 (p.

123). Another report found that ninety percent of the top quintile's increase in wealth accrued to just the

top one percent (p. xiii).

n 1999, for example, "'the richest 2.7 million Americans, the top 1 per cent, will

have as many after-tax dollars to spend as the bottom 100 million'" (p. 103)

class distinctions.

class distinctions.

http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/Econ_Articles/billionaires.html

1. Cost of living is typically the same for everyone. In a free market

economy, factors contributing to the cost of living will adjust so that poorest members of

the society are forced to spend all their income on bare necessities (food, housing,

medicine), whereas richer members will have enough excess income that they can save and

invest.

2. The process by which corporate officers are paid large salaries and

bonuses, the total compensation sometimes being as much as thirty thousand times as much

as that of their lower-paid employees. (Disconnect between a) officer performance and

compensation, and b) officer compensation and worker compensation, and that officers are

compensated at levels disproportionate to either performance or payroll because they are

already part of the elite, and that this is a self-perpetuating methodology to maintain an

elite class (see neofeudalism).

Phillips shows how the economic concentration that

corrupts the political process came about--namely, through exploiting public policies for

private gain. As he states with unflinching clarity: "Laissez-faire is a pretense.

Government power and preferment have been used by the rich, not shunned" (p. xiv).

WEALTH AND

DEMOCRACY: A POLITICAL HISTORY

OF THE AMERICAN RICH. By Kevin Phillips. New York: Broadway Books. 2002. Pp. xxii, 473.

$29.95.

3. If the economy of any country is organized in the interests of the

super-rich, or is a plutocracy

in which only the wealthy can hold government office, it should be expected that wealth

condensation will follow. Some critics contend a modern example of this is the current

executive of the U.S. In the

view of some critics (e.g. Paul Krugman) the tax policies of the Bush administration vastly favor the wealthy over the poor and

the middle class. The argument underlying this is that progressive

tax systems are being scrapped in favor of regressive tax

systems, driving wealth condensation (by allowing the wealthy to retain more of their

wealth as disposable and investable income.)

Millionaires

in Senate. http://www.wsws.org/articles/2003/jul2003/sen-j07.shtml

4..Illegal immingration of Poor Mexican lowering wage of poor American

workers.

5. Outsourcing and Export of Jobs overseas.

6. Bail outs and Subsidies. Dependence on govt largesse.

Firget rugged individualism or a merit-based culture.

7. after-tax income during 1977-1994 actually declined for the

lower three quintiles and increased by only four percent for the next-to-the-highest

quintile (p. 137). The real growth was at the top

8. Inheritance Tax

9. middle-class families have maintained their levels of economic

well-being only by "sen[ding] new waves of women into the labor markets" (p.

113). As a result, the United States now has "the world's highest ratio of two-income

households, with its hidden, de facto tax on time and families" (p. 113). Further

comparisons with other Western industrialized countries make the United States look even

worse: "[T]he typical American worked 350 hours more per year than the typical

European, the equivalent of nine work weeks" (p. 113). And for what? American wage

earners have "less pension and health coverage as well as ... the Industrial West's

least amount of vacation time, shortest maternity leaves, and shortest average notice of

termination" (p. 113; emphasis added).

10. Shredded social safety net . Almost half of American workers have no

pension coverage beyond Social Security. U.S. employers have

increasingly reduced their funding of employees' retirement,

11. The situation with health-care coverage is even worse. Phillips points

out that "only 26 percent of employees in the bottom 10 percent had health insurance

provided by their companies" (p. 133). Indeed, eighty-four percent of Americans

without health insurance are in families with at least one employed person (6)--a

situation with no counterpart in any other industrialized democracy.

http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-650249/Wealth-and-Democracy-A-Political.html

12. Cost of education.

13. Glorifiaction of wealth. Cnspicuous consunpotion.

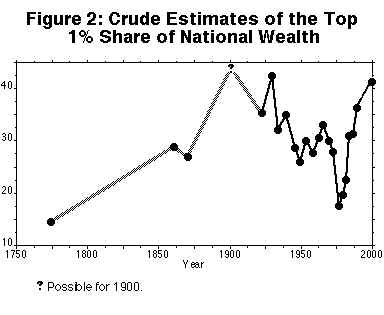

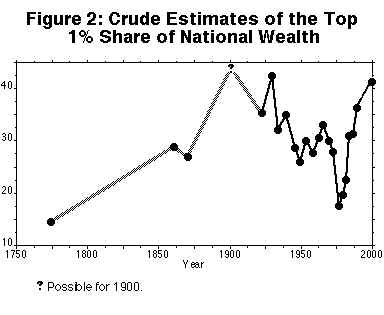

On the eve of the American Revolution, the United States-to-be had been a relatively

egalitarian society. The richest one percent of households owned perhaps fifteen percent

of the total wealth in

the economy&emdash;a very low value for such an inequality statistic. Even by the

immediae aftermath of the Civil War wealth was still not that

concentrated: the top one percent of households appear to have had a little more than a

quarter of the wealth

of the country.

By 1900, however, the U.S.

had become the Gilded Age country of industrial princes and immigrants living in tenements

of our political memory. On the one hand, Andrew Carnegie building the largest mansion in

Newport, Rhode Island with gold water faucets. On the other hand, 146 largely-immigrant

workers dying in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Manhattan because the exits

had been locked to keep workers from taking fabric out of the building for their own

clothes.

Surveys suggest that in 1929 the richest one percent of U.S. households held

something like 45 percent of national wealth, and that the concentration of wealth had been sharply

rising in the 1920s. We strongly suspect that World War I had seen substantial

deconcentration, as infiation eroded the value of bondholders' wealth and as high demand

for labor boosted workers' earnings. It is my guess that the second was stronger than the

first; that the concentration

of wealth was eroded

more during World War I than it was boosted in the 1920s, and that the concentration of wealth in the United

States peaked sometime in the twenty years before World War I, with the richest one

percent of households owning some 50% or so of total national wealth.

The distribution of income and wealth in the slaveholding

south had always been extraordinarily unequal: how could it be otherwise when one-third of

the population are held as chattels? But the distribution of income and wealth in the south did

not become much more equal after the Civil War. Blacks remained extraordinarily

impoverished relative to whites. And even southern whites were poor relative to northern

city dwellers or midwestern farmers.

World War I saw a sharp but short-lived compression of the income distribution. Wages

became much more equal in the space of a few short years. But this compression was quickly

undone in the 1920's, which saw "very unbalanced technological progress, with

productivity advancing faster in automobilesconsumer appliances, petrochemicals, and

electric utilities" then elsewhere in the economy. These sectors were skill-intensive

sectors. Relative skilled workers, both white collar and blue collar, once again captured

the lion's share of the increased incomes made possible by technological change. The

property income share also rose somewhat in the 1920's. It is uncertain whether relatively

poor and unskilled blue collar workers experienced any rise in their wages adjusted for

infiation between 1920 and 1929.

The Great Depression, World War II, and the immediate post-World War II period saw a

substantial levelling of the income distribution. Skilled urban workers earned ninety

percent more than unskilled workers before the Great Depression; they earned some sixty

percent more after World War II. Skilled manufacturing workers earned close to double what

unskilled workers earned before the Great Depression; they earned only forty percent more

after World War II. Similar patterns can be found in the share of income going to property

rather than to labor: it, too, dropped by a third&emdash;from thirty percent to twenty

percent of total national product&emdash;between the 1920's and the 1950's.

World War I saw a sharp but short-lived compression of the income distribution. Wages

became much more equal in the space of a few short years. But this compression was quickly

undone in the 1920's, which saw "very unbalanced technological progress, with

productivity advancing faster in automobilesconsumer appliances, petrochemicals, and

electric utilities" then elsewhere in the economy. These sectors were skill-intensive

sectors. Relative skilled workers, both white collar and blue collar, once again captured

the lion's share of the increased incomes made possible by technological change. The

property income share also rose somewhat in the 1920's. It is uncertain whether relatively

poor and unskilled blue collar workers experienced any rise in their wages adjusted for

infiation between 1920 and 1929.

The Great Depression, World War II, and the immediate post-World War II period saw a

substantial levelling of the income distribution. Skilled urban workers earned ninety

percent more than unskilled workers before the Great Depression; they earned some sixty

percent more after World War II. Skilled manufacturing workers earned close to double what

unskilled workers earned before the Great Depression; they earned only forty percent more

after World War II. Similar patterns can be found in the share of income going to property

rather than to labor: it, too, dropped by a third&emdash;from thirty percent to twenty

percent of total national product&emdash;between the 1920's and the 1950's.

The very rich need to be heavily taxed. If it hurts the

stock market for a while, so be it. The infrastructure

of America has too long been neglected. There are lots of

worthy public works programs that could be started.

Bridges are collapsing. Roads are caving in. But taxation

policies have too long allowed the very rich to make

more money than they can ever use.

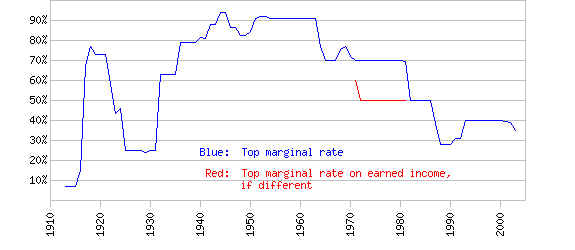

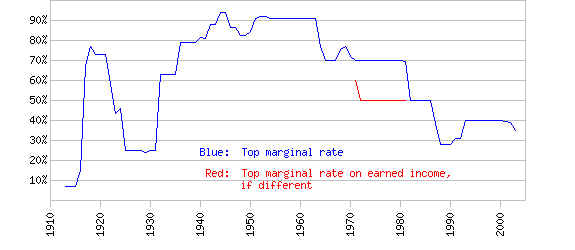

Top US Marginal Income Tax Rates, 1913--2003

Married Couples, Filing Jointly

Economic Boosts for A Sagging Economy.

Tax-cut monomania

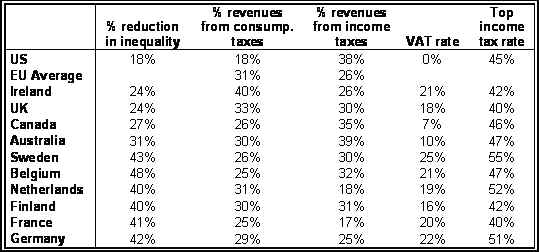

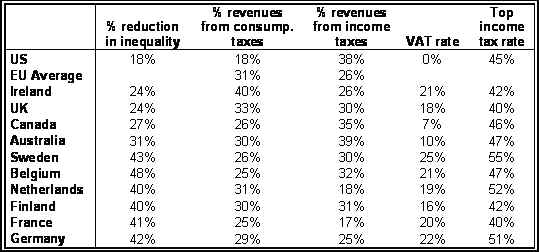

The striking thing to me is how little the US's tax code changes income inequality in the

US. Yes, the US tax code is progressive, so that disposable income after taxes is a bit

less unequal than it was before taxes... but the progressivity of the US tax code is quite

modest compared to other developed countries.

-----

The striking thing to me is how little the US's

tax code changes income inequality in the US. Yes, the US tax code is progressive, so that

disposable income after taxes is a bit less unequal than it was before taxes... but the

progressivity of the US tax code is quite modest compared to other developed countries.

http://angrybear.blogspot.com/2006/03/tax-progressivity-and-income_31.html

Gilded Once More

Many middle class families are one earner away from poverty.

As for the uninsured, their ranks grew in 2005 by 1.3 million people, to a record 46.6

million, or 15.9 percent.

greatest movement toward inequality occurred in the 1980s during the Reagan

administration,

For the other 91 million households, the median dropped, by half a percent, or $275.

Incomes for the under-65 crowd were hurt by a decline in wages and salaries among

full-time working men for the second year in a row, and among full-time working women for

the third straight year. In all, median income for the under-65 group was $2,000 lower in

2005 than in 2001, when the last recession bottomed out.

Despite the Bush-era expansion, the number of Americans living in poverty in 2005

— 37 million — was the same as in 2004. This is the first time the number has

not risen since 2000. But the share of the population now in poverty — 12.6 percent

— is still higher than at the trough of the last recession, when it was 11.7 percent.

2001 set in motion a complete phaseout of the estate tax. If the Bush administration

hadn’t been too clever by half, hiding the true cost of its tax cuts by making the

whole package expire at the end of 2010, we’d be well on our way toward becoming a

dynastic society.

Taxation has become much less progressive: according to estimates by the economists

Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, average tax rates on the richest 0.01 percent of

Americans have been cut in half since 1970, while taxes on the middle class have risen. In

particular, the unearned income of the wealthy — dividends and capital gains —

is now taxed at a lower rate than the earned income of most middle-class families.

Income inequality — which began rising at the same time that modern conservatism

began gaining political power — is now fully back to Gilded Age levels.

Last year, according to Institutional Investor’s Alpha magazine, James Simons, a

hedge fund manager, took home $1.7 billion, more than 38,000 times the average income. Two

other hedge fund managers also made more than $1 billion, and the top 25 combined made $14

billion. How much is $14 billion? It’s more than it would cost to provide

health care for a year to eight million children — the number of children in America

who, unlike children in any other advanced country, don’t have health insurance.

n the last quarter of a century when the United States moved from global power to

global behemoth, a quarter of a century in which American corporations reaped huge profits

while spreading their power and influence all over the globe, American workers made no

gains. None. The wages of American workers have, since 1978, been flat or declining.

lack of progressivity in the US tax structure is striking, and in my opinion,

disgraceful. For those who think something needs to be done to ameliorate the US's income

inequality problem, making the tax code more progressive should clearly be one of the

first lines of policy attack. There's a tremendous amount of room for improvement there.

All developed countries collect more - usually far more - of their tax revenue through

consumption taxes than does the US. Yet their tax codes are far more progressive. And

surprisingly, other countries do not create that tax code progressivity by simply levying

high marginal income tax rates on the rich; in general, their top rate is on par with that

of the US. Instead, they generate progressivity in the tax code through generous

low-income tax exemptions or credits, and top marginal tax rates that kick in at much

lower levels of income than in the US.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Medicare, Medicaid,

education,

child care and other vital programs, from

transportation to

health care,

the environment to

science research

"Trickle-down economics"

and "trickle-down theory," is a term used in political rhetoric to classify

economic policies that are perceived to primarily benefit the wealthy. The theory holds

that economic gains by the wealthy are spent by investment or purchases that result in

jobs for middle and lower class individuals.

The economist John

Kenneth Galbraith noted that "trickle-down economics" had been tried before

in the United States in the 1890s under the name "horse and sparrow theory":

"if you feed enough oats to the horse, some will pass through to feed the

sparrows." Galbraith claimed that the horse and sparrow theory was partly to blame

for the Panic

of 1896.[10]

Keynesians generally argue for broad fiscal

policies that are direct across the entire economy, not towards one specific group

Bush calls for $145 billion worth of tax incentives

for business investment and quick tax relief for

indiviiduals.

Source: http://www.alternet.org/workplace/62118/

Will

there be new business investment

if confidence is low? Will it end up being a tax

break mainly for business investment already

planned? On the individual side, will it give the

wealthy who will get the tax rebates any real

incentive to spend the money.

It

fails to address UNDER-CONSUMPTION

as a primary cause for the recession. Those who

get the money are not apt to spend it. An

immediate spending boost is needed.

"

|

A Prescription

for Middle Class Happiness

An important new book, from an eminent Ivy League economist,

sees brighter skies ahead for average Americans — if we get serious about confronting

excess at the top of America's income ladder

A Too Much review of

Falling Behind: How Rising Inequality Harms the Middle Class

By Robert H. Frank

University of California Press,

2007

By Sam Pizzigati

June 11, 2007

Should average Americans really worry about all those millions

pouring into corporate executive pockets?

“D.” Taylor, the top official at Nevada’s biggest

union, doesn’t particularly think so. He’s too busy bargaining middle class

wages for 60,000 hotel workers to spend much time fretting about the massive sums now

concentrating at the top of America’s economic ladder.

“We really don't care what the people in the executive branch

make,” Taylor last month told a reporter asking about CEO pay, “just as long as

our members and their families can share in the wealth and have decent pay and job

security.” |

all of them are also pledging to scale back the lavish tax cuts that George W. Bush

has bestowed upon our nation’s wealthiest. They’re eager, as Clinton puts it, to

“hit the restart button on the 21st century.”

In other words, as Frank puts it, we care about “relative consumption in

some domains more than others.” We care so much more that we’ll spend our time

and money on activities that enhance our comparative position at the expense of activities

that don’t.

Economist Robert H. Frank would beg to differ. To build a United

States where average Americans can live truly secure, satisfying lives, Frank advises in

his newly published Falling Behind: How Rising Inequality Harms the Middle Class,

fewer dollars — far fewer dollars — need to be pouring into rich people’s

pockets.

Frank’s perspective, in our contemporary political clime, smacks

of “class war.” But Bob Frank makes for an unlikely class warrior. He teaches at

Cornell University, in a top-notch Ivy League business school. He writes regularly for the

New York Times. He does textbooks. His Principles of Economics may soon

become an Econ 101 standard.

"I believe,” Kuttner writes, “that the American economy is in danger not

just of increasing economic and financial inequality. It is at risk of a 1929-scale

catastrophe.”

“In the mass deprivation of the 1930s,” he adds, “demagogues

and dictators abounded. It was a miracle that the Depression delivered Franklin Roosevelt

and an energizing of American popular institutions, rather than a home-grown Adolf Hitler.”

In other words, as Frank puts it, we care about “relative consumption in

some domains more than others.” We care so much more that we’ll spend our time

and money on activities that enhance our comparative position at the expense of activities

that don’t.

references:

http://72.14.253.104/search?q=cache:fQR7gOAqE0AJ:www.cipa-apex.org/toomuch/goodreads.html+concentration+of+wealth+US+history&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=53&gl=us&client=firefox-a

|

class distinctions.

class distinctions.